The mimosa piqued my interest last year. First, in a wintertime photo of Marché Bastille, then, in an instillation by London-based florist Fiona Fleur Studio, and finally, dried, in a large basket outside the Topanga Mall L’Occitane boutique.

Especially in the photos of Marché Bastille, the mimosa’s neon-yellow blooms were incredibly striking before the bleak Parisian produce selection.

Until last week, I had never seen or noticed fresh mimosas in Los Angeles. I went for a run around the Balboa Park golf course, serendipitously detoured from my usual route, and spotted a mimosa tree. Today,1 I foraged a bouquet to gift my friend Mary at our International Women’s Day lunch.

Mimosas are synonymous with International Women’s Day thanks to Teresa Mattei, communist deputy of Italy’s Constituent Assembly and anti-fascist champion. At age seventeen, Mattei was expelled from all Italian schools because of her fierce opposition to Mussolini’s anti-Jewish laws. Later, Mattei was a key player in the 1944 assassination of the “Philosopher of Fascism,” Giovanni Gentile.

Post World War II (or so the story goes), Mattei was tasked with choosing a symbolic flower for the Fette de la Donna.2 Since roses, violets, and lily-of-the-valley were too expensive or difficult to find in Italy, Mattei proposed the mimosa. It was inexpensive and plentiful in the countryside.3

If not for this post, I would be oblivious to this tree's chokehold on Europeans. In Los Angeles, our natural environment remains relatively unchanged throughout the year—palm trees are evergreen. Of course, I obsess over our hyper-seasonal produce, but I rarely associate flora with seasonal change. In regions with drastic seasonal variation, I can imagine how the mimosa’s emergence forcefully bids winter farewell. Her yellow flowers are a sign that spring is very near.

Sometime in the 18th century, the genus acacia found its way from Tasmania, Australia to Europe. As indicated by the mimosa illustrations of the 18th-century Delftware pictured above, the flora was welcomed with a warm embrace.

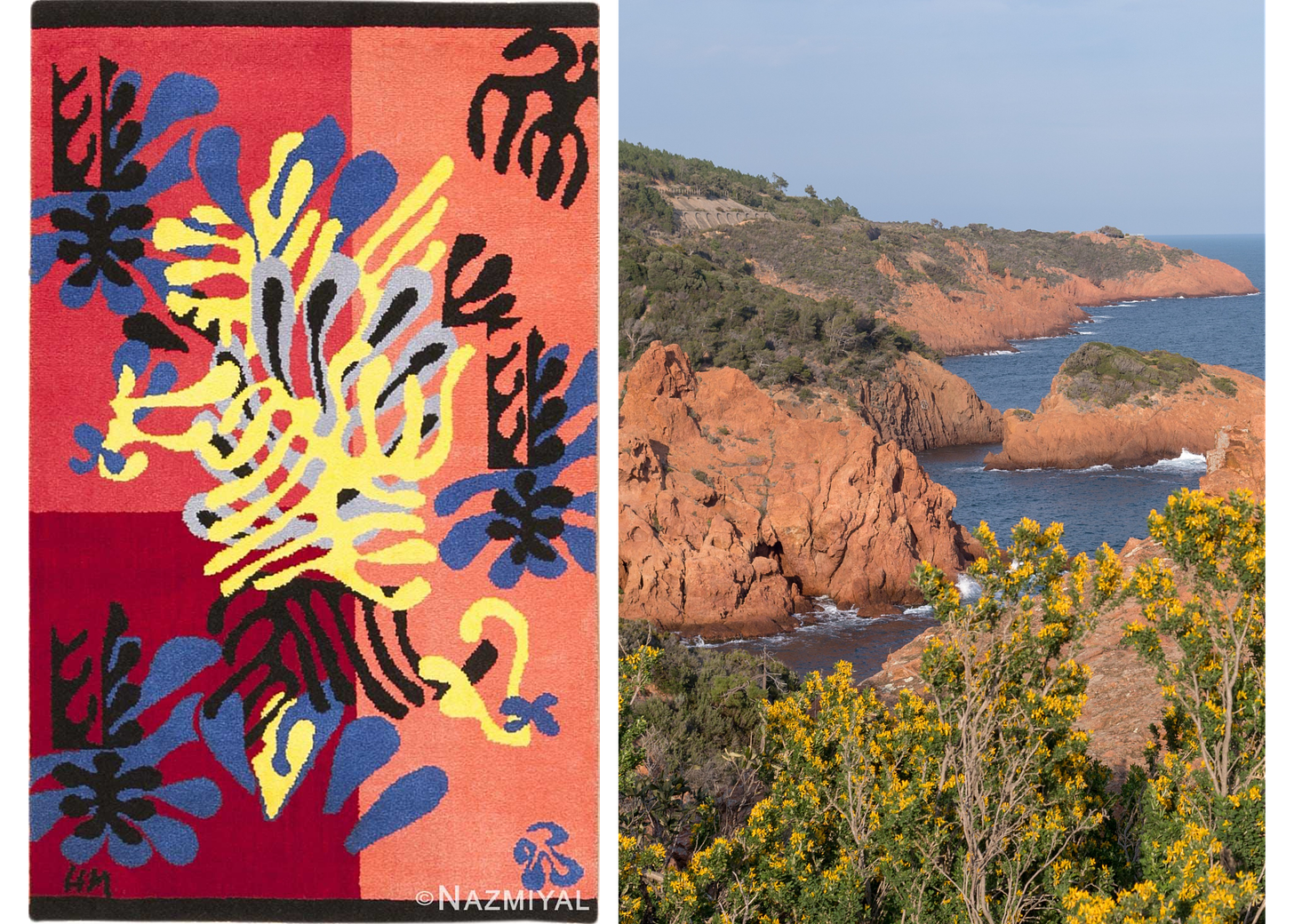

Nearly two hundred years later, Henri Matisse was captivated by mimosas as well. Designed between 1949 and 1951 for Alexander Smith Inc., his machine-woven Axminster wool carpet is the only carpet he ever designed or authorized.

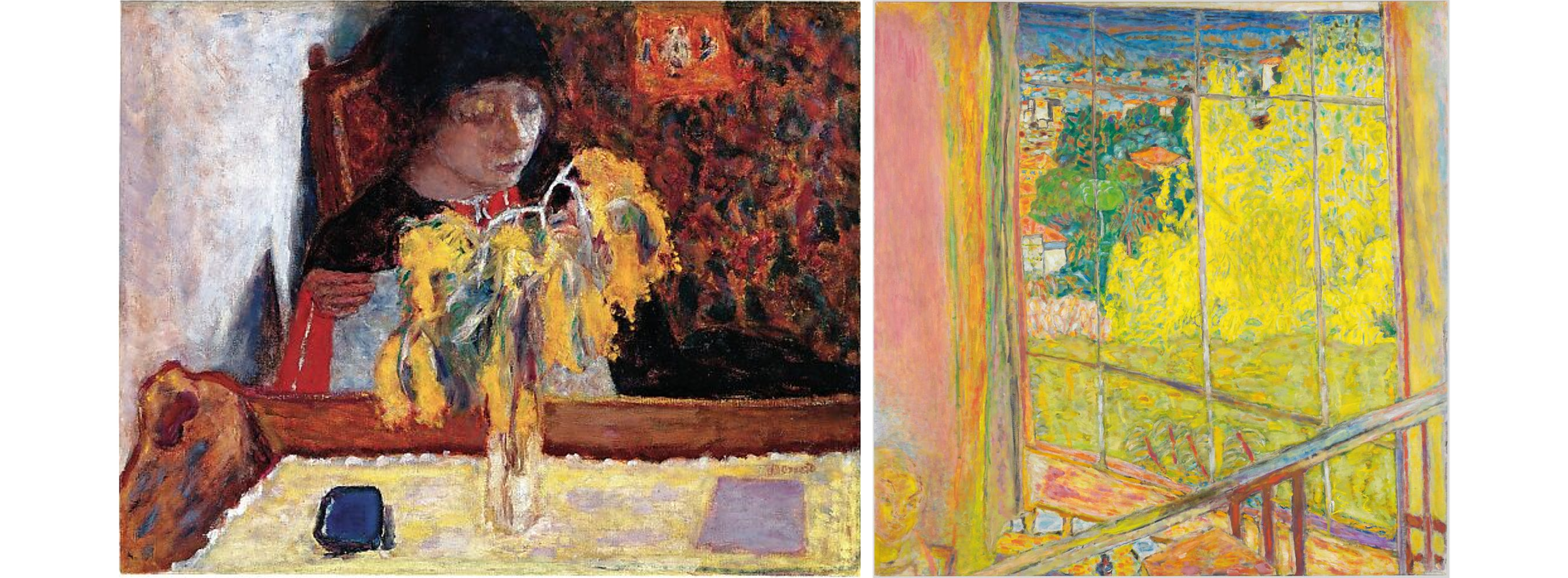

Pierre Bonnard, longtime friend of Matisse and fellow Côte d’Azur resident, features mimosas in several works. In Woman with Mimosa, the bright yellow blooms amplify the woman’s somber demeanor. Perhaps, it was placed in her lap as an antidote to seasonal depression. L'Atelier au mimosa, one of Bonnard’s last large-format paintings, depicts his Cannet studio view. On the lower left, his late wife Marthe’s face floats like a ghost.

Sur fond d’azur le voici, comme un personnage de la comédie italienne, avec un rien d’histrionisme saugrenu, poudré comme Pierrot, dans son costume à pois jaunes, le mimosa.

Francis Ponge, Le Mimosa (1946)

The opening line of Francis Ponge’s “Le Mimosa,” further illustrates the mimosa’s cultural presence. Ponge writes (and I translate), “Against an azure backdrop, here he is, like a character from an Italian comedy, with a bit of crazy histrionics, powdered like Pierrot, in his yellow polka-dot suit, the mimosa.” He continues, connecting mimosas to his sensual awakening.

I enjoy bejewelling my year with small, reliable traditions. Marigolds in early November, poinsettias in December, and now, mimosas in March. I hope you will, too.

[COVER IMAGE: Silver Wattle (Acacia dealbata) The Floral Cabinet, and Magazine of Exotic Botany, vol.3, (1840). From the Swallowtail Garden Seeds collection of botanical photographs and illustrations.]

Friday, March 8, 2024.

According to this article, post-World War II, Luigi Longo, deputy secretary of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), wanted to symbolize Fette de la Donna with a flower, inspired by the French tradition of gifting violets or lily-of-the-valley in celebration of International Women’s Day. I’m unsure if this is accurate. France did not formally celebrate International Women’s Day until 1982, though I suppose the article may reference an informal celebration.

Wikipedia’s International Women’s Day article references two sources in the footnotes. Unfortunately, I cannot access these files nor read Italian, so I am unable to fact-check the information.

Pacini, Patrizia (2011). La costituente: storia di Teresa Mattei (in Italian). Altreconomia, 2011. ISBN 978-8865160411.

Fantone, Laura; Franciosi, Ippolita (2005). (R)Esistenze: il passaggio della staffetta (in Italian). Morgana. ISBN 8889033312.